[ad_1]

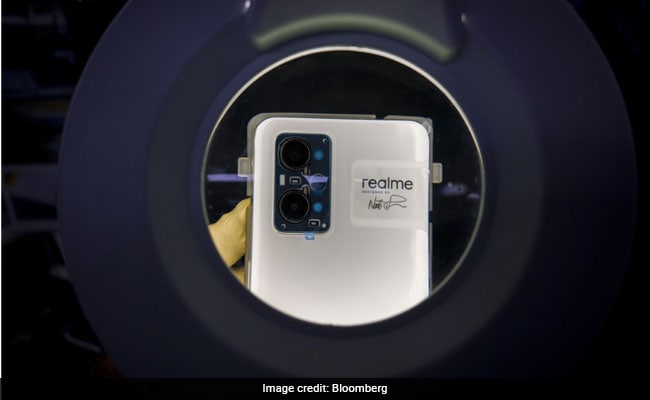

Realme In India: Realme has reached the No. 3 position in India with about 600 million smartphone users.

Last year, when a global chip shortage forced many smartphone makers to delay launches, upstart Chinese brand Realmetook a gambit in India. With processors from global giants such as Qualcomm Inc. in short supply, Realme decided to buy them from a relatively unknown Shanghai manufacturer to be able to keep churning out new handset models.

The move paid off, boosting the four-year-old newcomer’s sales and helping it reach the No. 3 position in the fast-growing market with about 600 million smartphone users. Only Samsung Electronics Co. and Xiaomi Corp. sold more devices in India in the latest quarter, with Realme closing in.

Closely held Realme has emerged as a force in the lucrative but treacherous Indian market where even global brands like Apple Inc. have struggled with regulatory hurdles. And in recent months, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration has heightened the scrutiny of Chinese companies as the two nuclear-armed nations clash politically.

Yet Realme has so far escaped the government crackdown unscathed. All smartphones it sells in India are built in the country, boosting local employment. And Realme is helping India bring new users online with its Android smartphones that can cost less than $100, a fraction of what iPhones and pricier Samsung models go for.

Realme In India: Realme has so far escaped the government crackdown unscathed.

“What I want to do is to bring more affordability to the India market,” Realme’s India boss Madhav Sheth said in an interview at a coffee shop next to the company’s local headquarters on the outskirts of New Delhi. Realme is in compliance with all Indian legal requirements and believes in cooperation with authorities, he said.

Realme’s relatively smooth sailing is in stark contrast with the obstacles its larger rivals have faced. Apple had to wrestle with the government for years just to open retail stores in the country and also had a protracted faceoff with authorities around a state-built spam-detection app that accesses users’ call logs. This year, the government cracked down on market leader Xiaomi with an anti-money-laundering agency moving to confiscate more than $700 million from the Chinese company, unnervingIndia’s entire fledgling electronics industry.

“Investing in India remains slightly risky for foreign companies as policies tend to change without enough of a forewarning,” said Shumita Deveshwar, senior director at investment strategy consultancy TS Lombard. “India has also been encouraging local companies to grow, and sometimes the politics of it makes the country an uncertain battleground, especially for foreign investors.”

Realme has taken advantage of rivals’ challenges by expanding its distribution to more than 40,000 stores and introducing aggressively priced devices such as last year’s 13,999 rupee ($180) Realme 8 5G, the cheapest fifth-generation wireless device at the time. Such tactics have helped it eat into Xiaomi and Samsung’s market share in India, said Tarun Pathak of tech researcher Counterpoint.

Realme commanded 16% of India’s smartphone market by shipment volumes in the first quarter of this year, up from 11% a year earlier. It only lags behind Samsung’s 20% and Xiaomi’s 23%, and was the only player to grow in double digits last year while rivals shrank, according to Counterpoint.

Realme In India: Realme has taken advantage of rivals’ challenges by expanding its distribution.

“Realme has held back the growth of Xiaomi and Samsung,” Mr Pathak said.

Samsung and Xiaomi representatives didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Encouraged by its gains, Realme unveiled its first global flagship store in Modi’s home state of Gujarat this month. The 13,000-square-foot space in the city of Ahmedabad is part of Realme’s plan to become more of a premium player in India. The company also envisages India as a step toward global expansion, and has recently entered European markets.

But Realme, with links to more established brand Oppo, must tread carefully in India where Chinese companies have had to bear the fallout from a border faceoff in 2020 between the countries. New Delhi has since banned more than 200 Chinese apps and tax authorities have raided smartphone players including Xiaomi and Oppo.

“India has a complex relationship with China and there is bound to be a certain level of government scrutiny of China-based companies,” said Amitendu Palit, senior research fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore. “If there’s a thaw in the frosty relationship between New Delhi and Beijing, we are likely to see some sense of normalcy coming back to business, but if the relationship continues to sour we might see it spilling over to business.”

At the same time, India has worked to give local companies a boost. In 2020, the government announced a nearly $7 billion plan to give financial incentives to increase local production and export of smartphones. A key element of that plan was to create “local champions” or smartphone giants that can not only cater to domestic customers but compete with the best in the world.

Yet homegrown smartphone players like Lava and Micromax have failed to capitalize on such incentives, with Realme and other foreign brands winning over more customers because of a perceived quality advantage. Realme stands out by combining low prices with upscale features, said Vijay Shankar Kriplani, a Mumbai-based marketing professional.

“A better battery life and lower price led me to switch to a Realme smartphone two months ago,” said Kriplani, 39, who previously used a Samsung device.

Realme, which like its rivals uses the glitz and glamour of Indian cricket and Bollywood to sell its smartphones, doesn’t want its success to be confined to just mobiles. Its India expansion strategy includes plans for the local assembly of tablets and laptops starting as early as this month. The company will also invest 100 million rupees to make wireless earphones, open a design studio and double its network of single-brand stores to 600 in two years, said Sheth. Those moves are expected to help Realme grow its sales 50% over two years, he said.

Still, with macroeconomic challenges intensifying and larger rivals to contend with, Realme will have a hard time sustaining its high level of growth, said Rushabh Doshi of tech consultancy Canalys.

“Realme has done well in India so far, but it has to brace for testing times ahead due to rising inflation, longer phone replacement cycles and as a global recession looms,” Doshi said. “Deep-pocketed players like Samsung have other businesses to fuel the growth of their smartphones units in this environment but smaller companies like Realme will probably have to tighten their purse strings and that’ll probably be their biggest challenge.”

[ad_2]